“When we pay attention to our senses, we inevitably find ourselves dead-center in the present moment of our lives.” ~ Dorje Lopön Charlotte Rotterdam

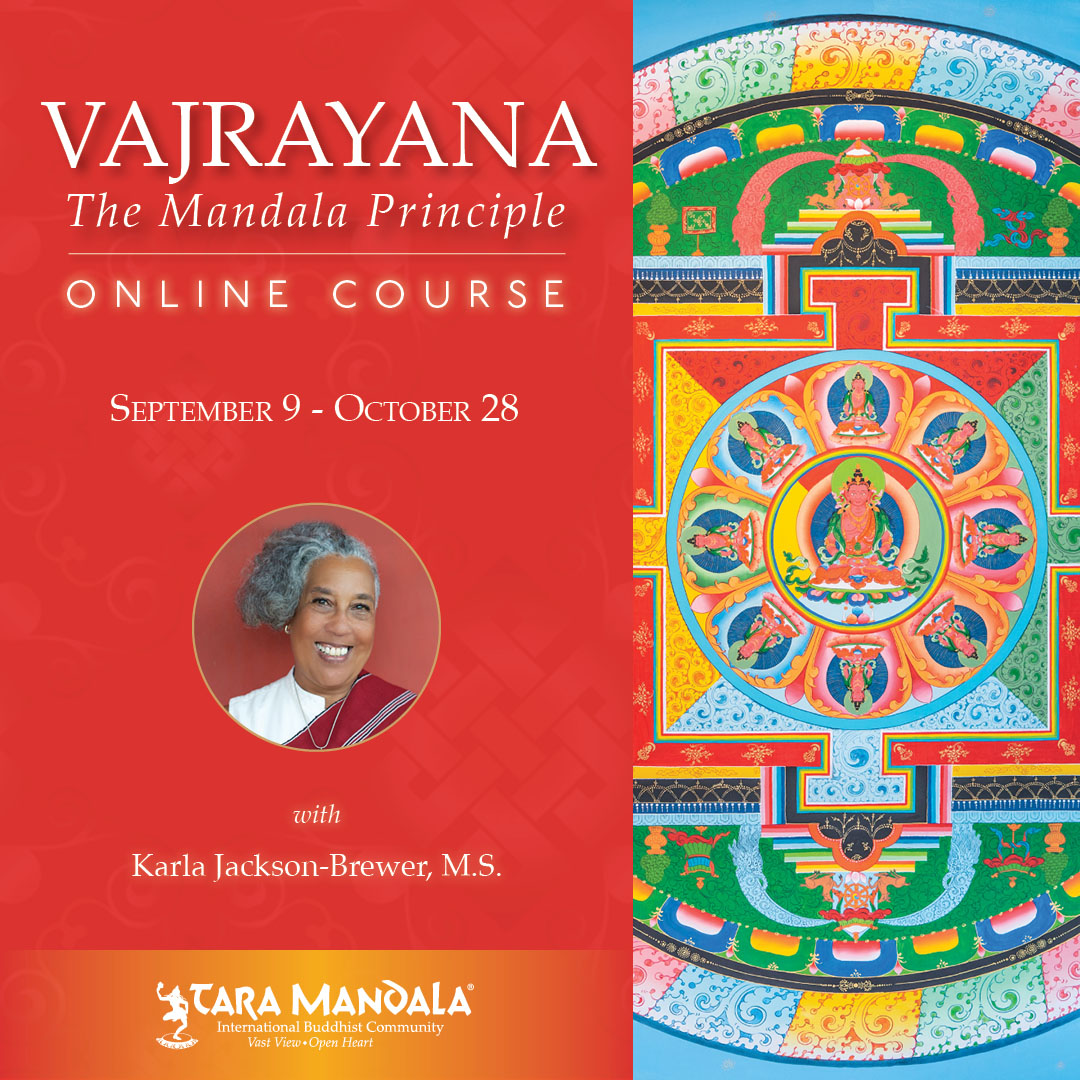

With the Vajrayana: The Mandala Principle Online Course beginning soon (September 9) led by Lopön Karla Jackson-Brewer, M.S., we share with you two blog posts from Lopön Charlotte Rotterdam emphasizing two key aspects to take with you into Vajrayana: the senses, and Vajra Pride.

To learn more and register for this online course, please click here.

The Practice of Savoring

In this blog post, Lopön Charlotte talks about how to bring the senses into practice: “Each practice introduces us to maha-sukha, the great bliss of timeless awareness, to radiant bodhicitta – awakened heart-mind – coursing through us.”

There’s a certain time of day when I get the nibbles – usually late afternoon but sometimes at night, right before bed. I open kitchen cabinets, the fridge, the chip drawer scanning what might satisfy me. But there’s something insatiable in my being. In reality I’m not really hungry, I’m not really looking for food. The salty cashews or sweet dark chocolate will take the edge off, but they don’t get to the heart of the matter.

That feeling of insatiability is perfectly represented in the hungry ghost, inhabitants of one of the six Buddhist realms of existence. With a huge extended belly and a tiny throat that lets almost nothing through, the hungry ghost is forever craving yet never satisfied.

The hungry ghost is the part of us that feels a fundamental lack or insufficiency, regardless of how much material wealth or outer success we actually have. As I mentioned in a previous post, it’s the state of mind that Chögyam Trungpa so aptly coined “poverty mentality.” When applied to the spiritual realm, the hungry ghost shows up as a continuous craving for more teachings, more practices, more transmissions; our impetus for deepening our spiritual journey comes not from a sense of joy but from a fear of missing out or not having enough.

Eating can be a powerful mindfulness practice because, if we are privileged, we have the opportunity to eat several times a day. Eating is at the core of our well-being. It’s a profound way that we interact with our world, taking in what is seemingly “outside” and making it “me.” It is a complete sensory experience; when we pay attention to our senses, we inevitably find ourselves dead-center in the present moment of our lives.

I share a mindful eating practice with my Naropa students in which we each receive one cracker, one almond, one piece of chocolate and one slice of orange. We approach these items as though for the first time, engaging them with all our sense perceptions: listening to the sound of spray emitted from the orange peel, following the creases of the almond with one’s finger tips, weighing the lightness of the cracker in the palm of one’s hand. By the time anything enters my mouth, I have come to know it quite intimately. Yesterday, I sat with the smallest bit of chocolate in my mouth, letting it dissolve slowly between my tongue and palate. An exquisite intensity of pleasure coursed from my mouth all through my body. How amazing! How full, how complete! From this experience of total satisfaction, the thought that I could chomp down numerous pieces of chocolate at a time seemed almost inconceivable.

Often we may feel we don’t have time to savor each bite of our food, or we simply forget because we’re busy doing something else. I once ate lunch with a group of Thich Nhat Hanh’s monks as part of a planning meeting; we ate without speaking a word and I became acutely aware of how my mind was madly rushing about wanting to engage them with my questions and concerns. Mindful eating is a practice of bringing awareness to each bite, letting the full array of tastes and aromas enter my mouth, nose, body. I try to remind myself not to pick up the next spoon-full of food before I’ve completely chewed, savored and swallowed what I have in my mouth. Each bite holds an invitation: Could I fully experience this? Could I be completely satisfied? Could this be enough?

I read a teaching from Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche once in which he encouraged us to sit down on our cushion before each practice with the thought that this could be the practice in which we completely awaken. It’s a radical thought but totally reasonable. If Buddha Nature is neither created nor destroyed, then our practice is “simply” to awaken to it, over and over again, and perhaps once and for all. Too often I notice how practice has become yet another self-improvement project that I’m slowly chipping away at. I busily write down how much of which practice I’ve accumulated, making sure I can progress to the next “level,” get to the next retreat. Too easily, I slip into the spiritual materialism which Trungpa warned of. Where is that oh-so-distant endpoint I’m trying to get to?

Really, any practice session can be complete, whole, enough. In the array of spiritual practices we have access to in our modern world, it can be helpful to remember that any one practice is all we need; any one practice is the doorway to totality. “To see a world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower,” William Blake reminds us. Just like the bliss produced by that piece of chocolate dissolving in my mouth, each practice introduces us to maha-sukha, the great bliss of timeless awareness, to radiant bodhicitta – awakened heart-mind – coursing through us. Regarding our true nature, “naturally occurring timeless awareness,” Longchenpa, the great 14th century Nyingma master, wrote “there is no need to strive for it elsewhere. It rests in and of itself, so do not seek it elsewhere” (The Precious Treasury of the Basic Space of Phenomena.)

The practice of savoring is an invitation to hold each moment in the potentiality of completeness, wholeness, whether in the mundane act of chewing a slice of orange or in the formal act of sitting meditation. In the act of savoring, the hungry ghost finally dissolves into the vibrant abundance that is always available to us.

Vajra Pride: Awakening Primordial Self-Esteem

In this blog post, Lopön Charlotte talks about how Vajra Pride is different from ordinary pride: “We are calling on the awakened heart which can be a mirror for the awakening of all hearts.”

I’ve always thought of Pride as one of the Seven Deadly Sins, right up there with Lust, Gluttony and Avarice. In the Buddhist tradition, pride is one of the five poisons, accompanied by a similar entourage of desire, jealousy, anger and ignorance. Pride, of course, evokes the image of a puffed-out chest, an overly confident bully who is concerned only with their own recognition, often at the expense of the well-being of others.

In Vajrayana deity practices, however, developing Vajra Pride is a critical component of the practice. I’ve been intrigued by how Vajra Pride might be different from our ordinary sense of pride, and why it is considered so important.

Ordinary pride is self-importance, a fixation on proving one’s status or value; there’s little or no room for the care of others, no space for humor or a lightness of heart. Ultimately, this kind of pride is based on a sense of lack, an anxiety regarding one’s own worth. We are generally distrustful of pride because we feel the vacuum of insecurity that lies underneath. This pride is unstable; like the emperor of the fairy tale, we suspect that beneath all the hype there’s just a naked old man.

Vajra Pride, in contrast, has nothing to prove but is based on trust in one’s inherent worth and value. Lama Tsultrim describes it as “primordial self-esteem.” It’s based on knowing our true nature – Buddha Nature – and having the confidence to act from this recognition.

Looking at a photo from the Civil Rights movement, I sense this primordial self-esteem mirrored in the faces of the young black men who sat at the whites-only diner counter. There is no aggression in their faces, only a self-assured and courageous presence in the awareness of their inherent right as human beings. There’s a quality of radiance that emanates from total, unflinching self-esteem that is deeply inspiring.

We can catch glimpses of healthy self-esteem in our daily lives, watching a dancer effortlessly glide through the air, listening to a musician take us into the delights of an improvised riff. We hope that the EMT and the surgeon will have this type of confidence unhampered by self-doubt or hesitation.

When we raise bodhicitta before our practice, aspiring to benefit all beings, we are invoking this primordial self-esteem. The bodhisattva does not vow to benefit their ten closest friends; they vow to benefit all beings, a completely irrational and wildly idealistic aspiration by any normal standards. We’re not calling on the half-hearted bodhisattva within us; this is not the time for false modesty. We are calling on the awakened heart which can be a mirror for the awakening of all hearts.

We’ve all experienced low self-esteem and the suffering of hesitation it engenders. Continuously monitoring whether or not we are getting approval (from the outer or inner critic), our thoughts and actions are awkward, misaligned, clumsy and ineffective. We’re driving with the brakes on.

When we relax the tension of trying to prove ourselves, we actually create the space for natural Vajra Pride to arise. Trungpa Rinpoche suggests that whereas “confused ego pride…is trying to become something else,” Vajra Pride is “facing the reality of one’s nature…being willing to be what one is.” There is, of course, incredible courage in this. We stand tall in our lives with basic confidence, simple clarity, and grounded fearlessness. Being of benefit – however that looks in our specific chapter of life – is not a chore but an inspired, joyful call, an expression of our awakened heart.

The key to Vajra Pride is its vajra-like nature: unfabricated, indestructible, primordial. This self-esteem is not built on a list of accomplishments; it’s not backed up by an illustrious CV. As Trungpa reminds us, “there is no need for compliments or acknowledgement…the question of poverty and richness has never been raised.” Vajra Pride is not built on our successes or broken by our failures. For a culture built on success and failure as the measure of our lives, the invitation of Vajra Pride is quite profound.

How, then, might we cultivate Vajra Pride?

• Deity practice: All Vajrayana deity practices involve visualization of ourselves as the deity; we visualize the details clearly, reflect on their symbolism, and invoke Vajra Pride, the “pride of the deity.” We really come to feel ourselves as the deity, embodying both the wisdom of interdependent emptiness and the skillful means of compassion. These practices are wonderful opportunities to try on the costume of Vajra Pride; their underlying purpose is to train us to move into our daily lives as the deity with the same inner, unshakable confidence, wisdom and compassion.

• Feeding your Demons: When self-doubt arises, we can recognize these as demons, not different from the maras that arose at key crossroads in the Buddha’s life. Feeding your demons can be a helpful way to work gently with these demons of insecurity, anxiety, fear and the various manifestations that our lack of inherent self-worth generates.

• Rest: Since Vajra Pride is primordial, it is perhaps best accessed not by straining more but by gently leaning back, relaxing more. We might contemplate who we are if we let all our accomplishments fall away. What remains when we drop all we have built up to prove our self-worth? The invitation to “just rest” counters our normal tendency to try harder, push further, do more. Rather than amping up our quest for confidence outside ourselves, we turn the searchlight inwards. Referring to our innermost wisdom, our true nature, the 9th century Indian teacher Aryadeva the Brahmin reminds us that “the meaning of the Prajna Paramita is not to be looked for elsewhere; it exists within yourself.” That means right now, just as you are, in this very moment without any manipulation. In that gentle and full presence we can experience the light of Vajra Pride shining brightly.

Vajrayana – The Mandala Principle

With Lopön Karla Jackson-Brewer, M.S. • September 9 – October 28

Our true wealth lies in that which is arising. In this sense, the teachings of Vajrayana are helpful, powerful, and always relevant. This online course is an 8-week in-depth historical and philosophical overview of Vajrayana and an exploration of the mandala principle as a guiding framework for understanding and embodying the richness of the Vajrayana path. With emphasis on sacred world and sacred view, the Tantric Buddhist path integrates all aspects of life, including the full range of sensory and sensual experience … Read more »

These blog posts are republished here with permission from Dorje Lopön Charlotte Rotterdam, via her Skymind website. Header: Artwork by Lama Gyurme